Are You Driving With Alzheimer's?

It can be scary when someone with Alzheimer’s won’t stop driving. Scary for them when they forget things they’ve known for a long time. Scary for someone in the car with them when they breeze past road signs without seeing them. Scary for others when they narrowly avoid an accident or hesitate at left turns for no reason.

Alzheimer's Impairs Driving

For someone who has driven for many years, driving can feel automatic. In reality, driving is a highly complex task that involves interaction between the brain, eyes and muscles. It requires complex thought processes, manual skills and fast reaction times. Alzheimer’s is more than memory loss. Alzheimer’s limits concentration, impairs judgement and causes vision and insight problems. Together, all of these things reduce a person's ability to drive safely.

People with Alzheimer's look the same on the outside, but on the inside, serious changes are happening. Driving with Alzheimer’s makes people:

• get lost in familiar places

• drive too close or too far away from other cars/objects

• drive at inappropriate speeds

• slow to react accurately to on-road conditions

No one wants to stop driving—including someone with Alzheimer’s. Driving makes people feel self-sufficient and independent. “Giving up driving” means relying on others to do what we used to do for ourselves. Having to ask someone for help getting somewhere can feel humiliating or like we have become “a burden.” In reality, the emotions we attach to driving are simply beliefs we’ve created. Recognizing this gives us the power to choose how we feel about not driving. As a family caregiver, you can steer the conversation to a positive place.

“Man is troubled not by events, but by the meaning he gives to them.” ― Epictetus

Alzheimer's Driving Myths

“Not Being Able To Drive Will Kill Him/Her”

No one has ever died because they stopped driving. When you hear someone say something like, “If he can’t drive, it will kill him,” recognize that emotions are talking, and not reality. Ask anyone who stopped driving. They’ll assure you they’re still very much alive.

“No One Can Tell Me I Can't Drive”

Driving is a privilege and not a right, even if some of us don’t see it that way. Your state's department of motor vehicles decides who can legally drive and who can’t. Everyone needs approval to drive—it's never simply the driver’s decision to get behind the wheel. Getting and keeping a driver’s license usually involves passing a vision test, passing a written test, sometimes passing an on-road skills test, and paying a fee. These requirements aren't optional—even for people with Alzheimer’s. In some instances, driving with Alzheimer's can require a medical re-examination, additional documentation and different tests.

“He's Still A Good Driver”

Good Drivers don't mind taking driving assessments. An on-road driving assessment from an accredited Occupational Therapist is the best way to assess driving skills for someone with Alzheimer's. Ask your doctor for a referral.

An Alzheimer’s diagnosis doesn’t always mean someone needs to stop driving immediately. But, everyone usually stops driving at some point—whether they have Alzheimer’s or not. When it’s time for someone with Alzheimer's to stop driving, as a caregiver, your attitude can set the tone. You can choose to mirror a devastating loss or reflect a wise decision. The key to a better transition is to change the story around not-driving.

What Can Family Caregivers Do?

STEP ONE: Learn The Early Warning Signs of Driving With Alzheimer's

Some people fighting Alzheimer’s continue to drive when it’s no longer safe for them to do so. Be aware of what’s changed for the person you love fighting Alzheimer’s. You know the difference between safe driving and unsafe driving. Look for the early warning signs of Alzheimer’s-impaired driving:

1) Inappropriate speed or stopping in traffic for no reason.

2) Confusion about when to stop or change lanes.

3) Getting lost in familiar places.

4) Driving the wrong direction.

5) Incorrect signaling.

6) Ignoring or forgetting what traffic lights and signs mean, like thinking ‘green’ means stop and ‘red’ means go.

7) Relying on a passenger or “co-driver” to navigate.

8) Refusing passengers like family and friends.

9) Getting nervous or irritated about driving.

10) Risky on road judgment, like avoiding near misses, not braking in time, or driving too fast in bad weather.

11) Poor eye, hand, leg coordination and reflexes.

12) Getting more traffic tickets or police warnings.

13) More small dents or scrapes on the person’s vehicle from misjudging widths and distances.

STEP TWO: Talk About NOT Driving

The best case scenario for someone with Alzheimer’s is to voluntarily stop driving. If your loved one is open to this idea, they may simply decide to stop driving. Sometimes, the It’s-Time-To-Stop-Driving conversation can be easier after an Alzheimer's diagnosis. If your loved one recognizes they are impaired from Alzheimer’s, and understand what’s at stake, they may be willing to stop driving on their own. That's not the case for everyone.

81% of people with Alzheimer’s also experience something called anosognosia. From the outside, anosognosia looks like denial or stubbornness, but it’s more than that. It is a lack of awareness that they have any impairment whatsoever. Anosognosia is a neurological disorder that makes it impossible for someone with Alzheimer’s to believe they need help. In their mind, nothing's wrong with them.

Best Case Scenario

The best case scenario for driving with Alzheimer’s is not being noticed. No road rage. No “accidentally” clipping someone's bumper or hitting a pole. No driving too slow or too fast. No forgetting where you’re going or how to get home. No freezing in the left hand turn lane. No accidents and no traffic tickets. This is standard stuff for unimpaired drivers, but for someone with Alzheimer’s, these things become increasingly difficult over time. And more importantly, without any forewarning. Driving with Alzheimer’s puts everyone in the car and on the road at risk.

The Worst Case Scenario

The worst case scenario for driving with Alzheimer’s is an accident with injuries that aren't covered by insurance. Automobile insurance companies require something called, “full disclosure” prior to granting coverage. This means it's your responsibility to disclose anything that could impair your ability to drive safely. The worst plan for driving with Alzheimer’s is hiding the diagnosis. Accidents are a sure way to bring driving with Alzheimer's out into the open — especially accidents with injuries. Drivers who neglect to disclose a cognitive impairment (no matter how mild) to their insurance provider, risk being classified as “uninsured” when an accident occurs.

For people driving with Alzheimer's, paying out of pocket for an auto accident can be financially devastating— especially accidents with injuries. This might not be a motivator for someone with Alzheimer’s, but it should be for a family caregiver. Why? Family caregivers will bear the brunt of dealing with insurance companies and attorneys. Don’t let preventable car accidents or out of pocket medical bills drain your savings when you need it the most.

Today is the best day to talk about not-driving to a loved one with Alzheimer’s. Everyone has a tendency to put unpleasant conversations off, or wait for “the right time.” Include family members and/or friends to support the not-driving conversation. Whether in group conversations, or privately with your loved one, make sure family and friends support the idea of your loved one not-driving.

Ask your doctor if it's time to stop driving with Alzheimer's

Call ahead of your next appointment and share your concerns, privately. The doctor isn’t in the car and doesn’t know what is/isn’t happening behind the wheel. Let them in on what driving with Alzheimer’s is like for you and your loved one.

Alzheimer’s gets worse over time, not better. There will never be a good time to talk about not-driving. No one fighting Alzheimer’s is magically more receptive to not-driving in the future. Especially someone who doesn't think that they have Alzheimer's. If your loved one is in the early or early/middle stage of Alzheimer’s, there’s a chance you can get through to them and they can decide to stop driving on their own.

Tips For Talking About Not-Driving With Alzheimer's

- Talk about not-driving as soon as possible after diagnosis.

- Have the conversation when everyone is calm.

- Time discussions with medication or health status changes.

- Make conversations short and frequent.

- Concentrate on the person’s strengths and what they can do.

- Discuss the positive aspects of their other options.

- Be empathetic and acknowledge that not-driving is a big change.

- Normalize the situation by talking about others who had to make a similar decision.

- Acknowledge that many people with Alzheimer’s have a history of safe driving.

- Focus on the financial benefits of selling their car.

- Be respectful and try to understand how your loved one is feeling.

CHECKLIST: Tips For Talking About Not-Driving

When Talking Doesn't Work

STEP THREE: 6 Ways To Help Someone Stop Driving

If someone with Alzheimer’s refuses to stop driving voluntarily, you still have options. Passive strategies can work if your loved one is in the early to early/middle stages. Changes to their thinking in these stages lower their:

- tolerance for frustration

- ability to recognize objects

- ability to retrace their steps

Early/middle stage changes make inconvenience, distraction and postponement effective strategies to help your loved one stop driving. Passive strategies are similar to the idea behind the Japanese art of self-defense, Aikido . First, they utilize the principle of nonresistance, and second, they help your loved one's dementia to work in your favor.

If your loved one is used to being “the one who drives,” not-driving represents a huge change to something that’s been automatic for years. Projecting confidence about them not-driving will help them feel confident too. People with Alzheimer's are highly influenced by their caregiver's attitude. It takes time to replace an old routine with a new one. Be patient.

1. Be Politely Unhelpful

1. Be Politely Unhelpful

Memory issues are usually the first sign of cognitive impairment. How many times has your loved one “lost their keys?” Next time, instead of helping them find their keys, be attentive, but stay put and say,

“I haven’t seen your keys.”

Keep putting the ball back in their court. Ask them where they last saw their keys? Be too busy doing something to help them look. They could lose interest or forget what they were looking for.

2. Limit Their Access

2. Limit Their Access

If there are spare keys to your loved one’s vehicle, hide them. Don’t keep one on your key ring. If your loved one can’t find their car keys, they may ask to borrow yours. Respond by saying,

“I’m not sure where my spare key is.”

Lose the spare key “permanently” in a place your loved one will never look. (Just don’t make it such a secret place that you forget where they are!)

3. Offer To Drive

3. Offer To Drive

If someone fighting Alzheimer's wants to drive you somewhere in their car, offer to drive them in your car instead. Get your car keys and encourage them to go with you by saying,

“I’ll drive.”

Always offer to drive them in your car, until it becomes automatic for both of you. This will help them get used to not using their car, and not driving it.

4. Make Your Car Hard For Them To Drive

4. Make Your Car Hard For Them To Drive

Discourage them from driving your car by making it harder to get in. For example, if your loved one is taller than you are, make sure the seat is as close to the steering wheel as possible. Do not offer to adjust it. If they get frustrated and ask you what's wrong with your car, simply say,

“I need to fix that. I'll drive.”

Make driving your car as inconvenient as possible for them.

5. Agree & Postpone

5. Agree & Postpone

People fighting Alzheimer’s need validation just like the rest of us. The person you love fighting Alzheimer's is probably sick and tired of making mistakes and being “corrected” all the time. Agreeing with what they want to do or what they're saying is an easy way to validate their “thinking” and suggestions. It doesn't matter if it's a bad idea or even if you're ever going to go along with it. By the time you get around to doing it, they will have forgotten.

6. Get A “DO NOT DRIVE” Prescription

6. Get A “DO NOT DRIVE” Prescription

Ask your doctor for a “DO NOT DRIVE” prescription. Your doctor can write “DO NOT DRIVE” on a prescription pad for you to take home and put on the fridge. Then, you can refer to it when you’re loved one wants to drive by saying,

“The doctor said you can’t drive.”

It seems ludicrous that something this simple works, but if your loved one (still) respects authority and follows rules, it does. If it doesn't work the first time, don't be afraid to try it again, because your loved one might not remember seeing it before. Even if it doesn't work now, it might work in the future, so don't throw away your “DO NOT DRIVE” prescription. They key is for you to act as if the “DO NOT DRIVE” prescription is as real as a medication prescription. Your loved one takes their cues from you—if you make it serious, it will be.

STEP FOUR: Request A Driving Evaluation

If the “DO NOT DRIVE” prescription doesn’t work, ask your doctor for a referral for a driving evaluation by an Occupational Therapist. Occupational therapy for Alzheimer’s disease is a covered service under Medicare and many other private insurance providers.

Occupational Therapists have specialty training and experience in driver rehabilitation. A driving evaluation by an Occupational Therapist has three parts:

- Medical and Driving History Screening

- Skills Evaluation (physical, visual, perceptual and cognitive)

- Behind-The-Wheel Assessment

If your doctor can’t help you find an Occupational Therapist for a driving evaluation in your area, contact The American Occupational Therapy Association.

This evaluation will clear up any questions about your loved one’s driving abilities. If they fail this specialized evaluation, you will have written documentation that they are no longer safe to drive. Be sure to make extra copies (should the original happen to get misplaced or mistakenly shredded). Copies should be sent to:

- Your state’s driver’s licensing department

- Your automobile insurance company

- Your local police department

If your loved one’s license is suspended, this means they will no longer be able to legally drive in your state.

Be safe. Avoid expensive accident repairs or medical bills. Don’t go driving with Alzheimer’s.

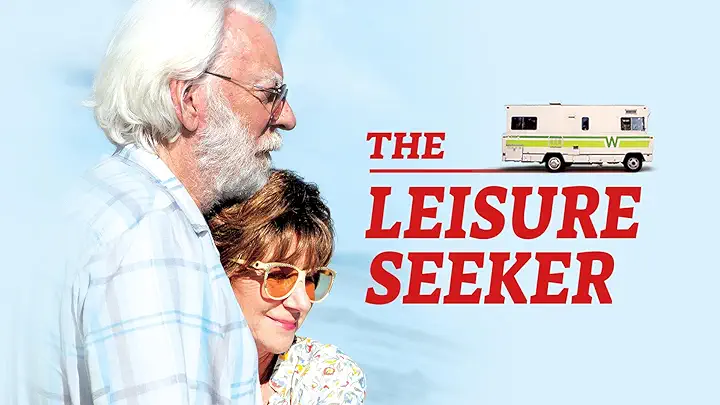

BONUS STEP: Change Your Perspective. Watch A Movie.

Sometimes, watching a slice of other people’s lives helps us make better decisions in our own lives.

Join Helen Mirren and Donald Sutherland in, THE LEISURE SEEKER:

A long-married husband and wife take off for one last trip in their 1975 Winnebago Indian motorhome before his Alzheimer’s and her cancer catch up to them.

Run Time: 1 hour, 53 mins

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT DEMENTIA AND DRIVING, Alzheimer Society of Canada

DEMENTIA AND DRIVING, Dementia Australia

DRIVING EVALUATIONS BY AN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPIST, The American Occupational Therapy Association

THE FIT TO DRIVE TEST FOR DEMENTIA PATIENTS, The Alzheimer’s Reading Room

THE HARTFORD CENTER FOR MATURE MARKET EXCELLENCE, The Hartford